Beirut’s environmental degradation has left communities detached from nature and surrounded by pollution. However, Beirut has recently seen a growth in small green projects implemented in abandoned public areas, with volunteer groups attempting to mitigate the pollution of urban living.

“TheOtherForest” an initiative led by Adib Dada, aims to focus on nature as a tool for ecological regeneration in cities and will follow in the footsteps of Dada’s brainchild at Sin al-Fil, which was once Lebanon’s first urban forest.

According to a Greenpeace report this year, Lebanon has one of the highest levels of air pollution in the Middle East and North Africa.

The report also highlighted that Lebanon suffers from the highest rate of premature deaths in the region due to air pollution.

The country’s burning of Heavy Fuel Oil in power plants, unfiltered generators, and endless traffic fumes have increased levels of nitrogen oxide particles in the air, which is a dangerous pollutant released when fuel is burned and can cause respiratory problems and damage to the lungs.

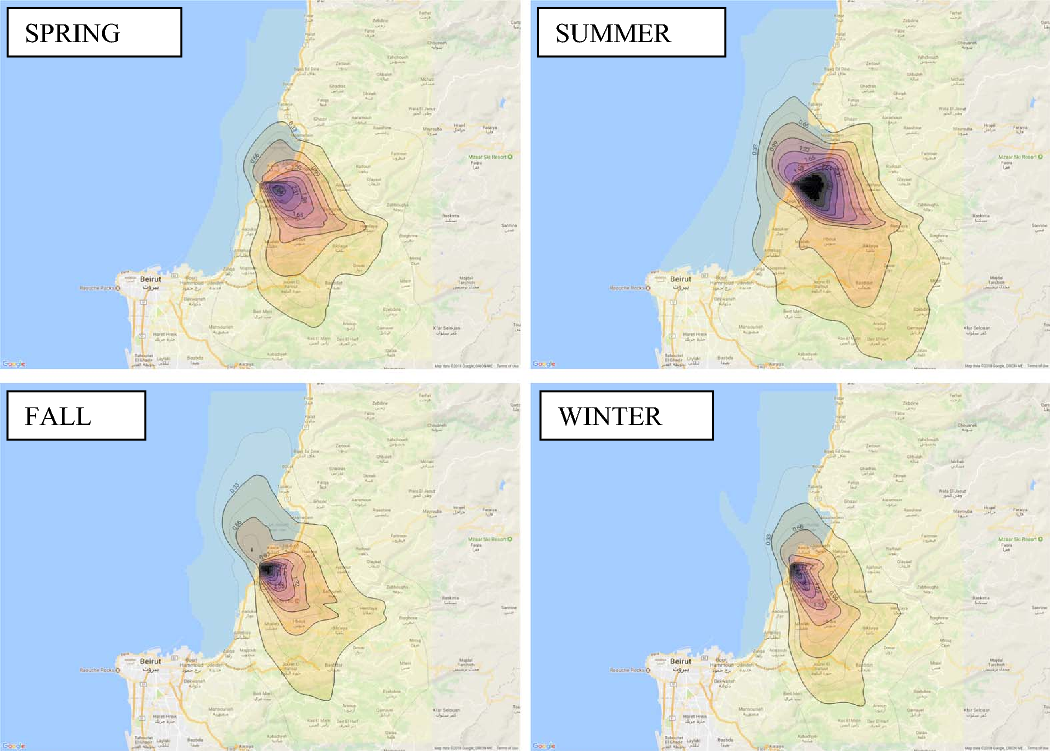

According to Greenpeace’s air pollution report of 2018, Jounieh is the most polluted town in Lebanon and listed as the fifth-most-polluted in the region. The town’s location beside the highway and the impact of the power plant have been factors in the city’s poor environmental standing.

Adib Dada partnered with the social enterprise, Afforestt, to plant over 1,200 trees and shrubs from 17 different native species in Beirut.

In 2019, fifteen passionate participants revived a 200-square-meter area with the support of the Sin el-Fil Municipality.

The area was chosen specifically for its location next to the river, which since its enclosure in concrete in 1968 has been cut off from the local community and became a heavily polluted dumping ground.

“The whole point is we are planting native forests, bringing back this ecosystem that used to exist here and disappeared because of urbanization. We are replicating and bringing it back into these urban landfills,” Adib Dada said in a statement.

“TheOtherForest” initiative adopts the Miyawaki technique, a method developed in Japan to return native species to areas affected by deforestation or cities in need of an environmental boost.

Through utilizing the innovative Miyawaki Technique, the created forests will be 100% more biodiverse, 30 times denser, growing 10 times faster, and absorbing noise and pollution 30 times more efficiently, than conventional man-made forests.

In our forests, we do not use chemicals to remove unwanted weeds. De-weeding is done by manually pulling these grasses and unwanted wild plants from the roots and away from the forest floor. This is to ensure that the roots of the weeds do not suffocate the growing native species. ~ TheOtherForest

After Sin el-fil, “TheOtherForest” was led to Zouk Mosbeh by a resident who reached out to Dada on social media. Karelle Rizk, a 29-year-old sustainability researcher, has been living with the detrimental effects of Lebanon’s biggest power plant her whole life.

Back in March, Dada and Rizk carried their idea of an urban forest in Zouk Mosbeh to the mayor, Abdo Elias El Hajj, who welcomed it.

However, the pair underwent eight months of phone calls and unanswered messages before they got the green light and could start fundraising.

According to Rizk and her father Wilson Rizk, a 74-year-old hydrologist and environmental expert who also lives in Zouk Mosbeh, the HFO burned in Zouk Mosbeh has a sulfur content of 6 percent, far exceeding the internationally recommended limit of 0.5 percent.

The sulfur-rich fumes also cause acid rain, resulting in ecological damage to open water and trees.

Thus, the air from the rubbish dump was so poisonous that it left Rizk’s father with a fever for five days and permanent damage to his voice, which is now strained and gravelly.

Yet, even with all the setbacks, work has finally commenced last week at the site of the new project in Zouk Mosbeh, the first stage of Dada’s afforestation process.

If all goes to plan for the pilot project in Zouk Mosbeh, Dada and Rizk hope to create further spaces in the town to alleviate decades of dirty fumes.

Dada explained the privileges of working with municipalities on a lower level of government, which has enabled permission to be granted for the schemes, even though it comes with delays.

Nevertheless, until the environment becomes a top concern for the government, the Lebanese people will have to endure the perils of toxic air for years to come and none more so than the residents of Zouk Mosbeh.

The afforestation projects are one aspect of Adib Dada’s work in climate action, architecture, and consultancy to provide an alternative approach to sustainability through invoking new relationships between climate, landscape, and inhabitants.