By December 2020, an increase of 51% in domestic violence calls was recorded by the Internal Security Forces (ISF)’s hotline.

The pandemic has come to tremendously shed light on domestic violence in Lebanon, with the ISF figures coinciding with the 16-day international campaign of the UN to end gender-based violence.

The report also noted that 14% of the abused women are minors under 18.

Unfortunately, the coronavirus-induced lockdowns, meant to keep people safe from the virus, have in turn trapped vulnerable women with their abusers at homes.

Locked at home, a place that should be a safe haven for individuals turned out to be a new form of torture. Local NGOs have also recorded an increase in calls for help from victims reaching out to them by phone.

The 24/7 support center of the local NGO KAFA Enough Violence, for instance, recorded an abrupt rise in the number of phone calls for help since the authorities implemented a lockdown back in March.

In just two months on the pandemic, calls rose from 299 at the beginning to 938 in May to then topping 1,000 calls a month.

KAFA’s director Zoya Rouhana told The Daily Star that “when people are stuck in their houses, with no alternatives, any man that has the potential to use violence to subjugate his wife will do it. And this will be exacerbated when economic and living conditions get worse.”

As Lebanon endures its worst economic crisis since the Civil War, and the local currency losing 80% of its value, prices of basic necessities have tripled, and unemployment rates have increased.

That has ensued with more breadwinners, usually men according to the patriarchal role, mulling in anger and frustration at home.

Adding to the pandemic and economic issues, women’s fate in Lebanon is tied to personal status laws of their sects, whereas little to no rights is granted to them, including protection.

The 15 separate sectarian courts that exist in Lebanon and rule over family affairs, which include marriage, divorce, and child custody, are run by men and favor men in their rulings.

The consequences have been catastrophic in Lebanon, leaving women in dangerous situations of domestic violence and with very limited rights for divorce, financial support, and even to keep or protect their kids.

After years of activists campaigning, the government finally created Law 293 in 2014 to protect victims of domestic violence. However, women in financial duress, or lacking funds for being housewives, aka relying on their husbands for all that is finances, have been incapable to seek that law.

According to AUB’s Policy Brief, filing a case against an abusive husband would require economic empowerment that is absent among most of the abused women.

Abused women lack an alternative economic resource in case of the absence of their husband, or outside the marital house.

Another active NGO that has been endeavoring for women’s rights and protection is Abaad. Since 2004, the NGO has been providing ISF officers with training on how to deal with gender-based violence (GVB). It has also been assisting the ISF domestic violence hotline team.

Raghida Ghamlouch, program manager at Abaad, told The Daily Star that “for a long time, there was a lack of knowledge and sensitivity on the subject of GVB, and how to deal with victims.”

Launched in 2018, the ISF hotline 1745 was a decisive move towards protecting women in abusive marriages or homes. It has been even more needed now during the lockdowns as it has become the only resource since mobility has been restricted.

That hotline has received 1,120 calls of domestic violence complaints, from February to November, a staggering increase of 102% compared to the same period last year, according to the ISF.

That is in addition to KAFA’s hotline recording over 1,000 calls in the months of July, September, and October of 2020.

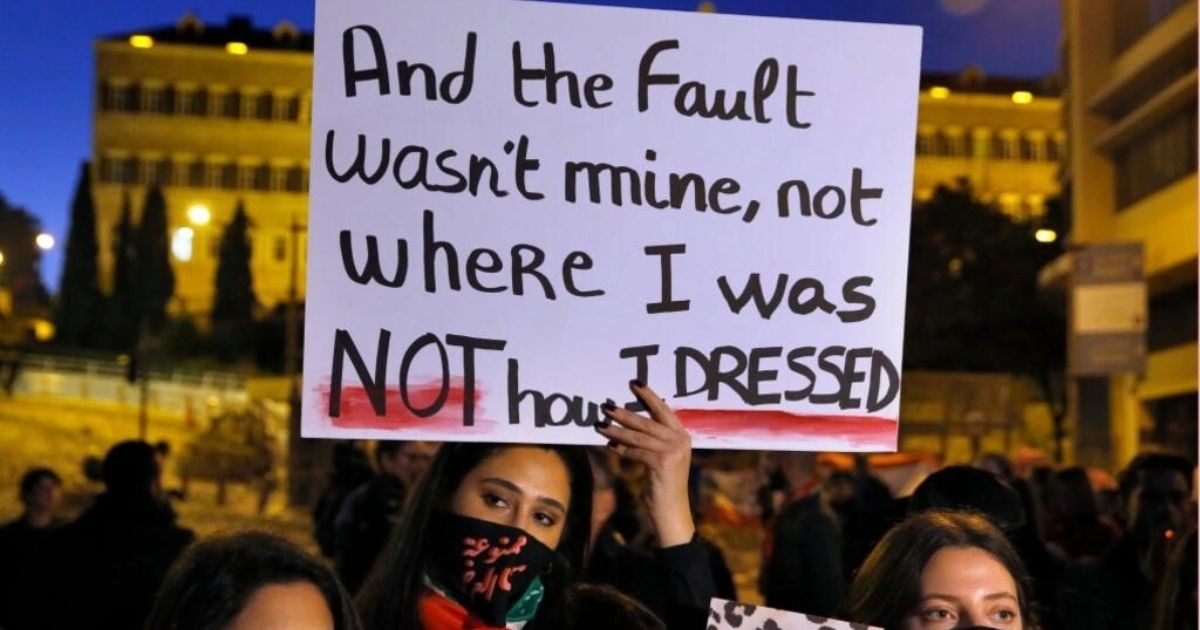

KAFA’s director Rouhana explained that “the issue of violence against women was totally fraught in Lebanese society” in the 1990s when she initiated her campaign for women’s rights.

Her campaign included, and still does, bringing awareness to the society on that issue as well as women’s rights, encouraging women to speak out.

“It is a very long struggle. Maybe it is easier to change laws. But, to change society and culture, that is an even longer obstacle.” she admitted.