Lebanese-American freelance journalist Lisa Khoury has been traveling to Lebanon for the past three years to report on humanitarian issues.

She has written for various channels, such as ABC News, Al Jazeera, Vox, and more. One of her most recent reports for Washington Monthly details the horrors of the kafala system in Lebanon.

Horror stories from Lebanon

In Lebanon, Khoury met 33-year-old Josephine Adotey from Ghana, who had once tried to kill herself in attempts to escape her employer’s abuse.

Adotey’s boss overworked her, starved her, and made her sleep on the kitchen floor, for a wage of $200/month. He had even tried to rape her and threatened to kill her if she told anyone, Khoury reported.

The Ghanaian moved on to another employer, a Lebanese woman, who was even more abusive. When she tried to quit, her employer refused, saying she had “bought her.”

Another appalling story is that of Constance who, upon arrival in Lebanon, learned she was pregnant. The recruitment agency refused her request to go back home to have the baby.

They gave her two choices: pay them back for the cost of bringing her to Lebanon or get an abortion. She had no money… and consequently had no choice. She says she is just praying for forgiveness.

And let’s not forget Faustina Tay, whose death was ruled a suicide, despite suggestions that she may have been killed.

Quoting a caseworker of the NGO This is Lebanon, Khoury wrote: “Faustina is our George Floyd. And every week, two George Floyds die. In Lebanon, Black lives don’t matter.”

“Actually, to Lebanese leaders, no lives appear to matter, immigrant and native Lebanese,” Khoury wrote, before highlighting the Beirut blast, which was a direct result of government corruption and negligence.

The government doesn’t care

“The Lebanese government has proven that it cannot protect nor fulfill the rights of any of the people living in Lebanon — be them Lebanese or migrants or refugees,” said Diala Haidar of Amnesty International.

Yet, as little as Lebanese lives matter to the country’s leaders, migrants’ lives seem to even matter less. Khoury blames the Lebanese government for refusing to protect migrant domestic workers.

Lebanon’s labor law specifically excludes migrant domestic workers, stripping them of “labor protections, like minimum wage, rest hours, or overtime compensation,” Khoury reported.

When caretaker Labor Ministry Lamia Yammine announced a unified contract for migrant domestic workers, a top administrative court in Lebanon suspended it. Apparently, it wouldn’t have suited the business of the recruitment agencies.

Additionally, with the dollar shortage, many migrant domestic workers are being left to work for no pay. Those lucky enough have been sent back home, but others are still struggling in Lebanon, where the pandemic is also an issue.

“It’s important to note many families treat their maids with dignity. Some buy them cell phones, health insurance, clothes, and include them at the dinner table,” Khoury assured.

“Moreover, it makes sense for Lebanese to have maids. The country hardly has daycare facilities or nursing homes, and families with children and elderly parents need help.”

“But with leaders refusing to legally protect them, all maids can rely on is their employer’s goodwill.”

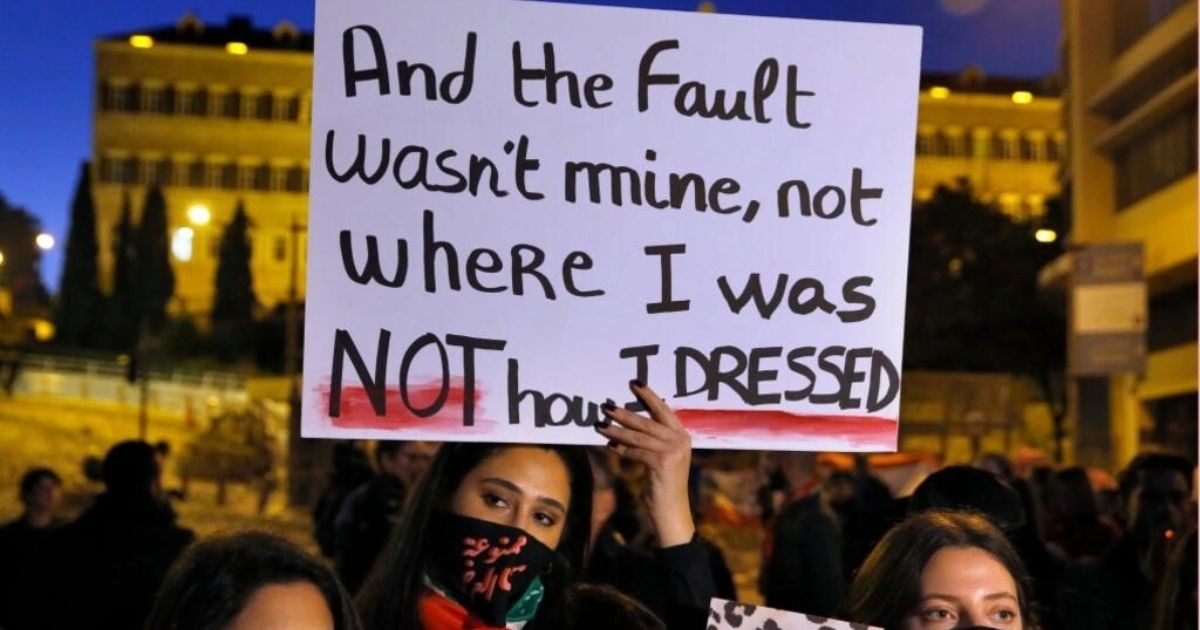

However, after the birth of the Lebanese uprising, Khoury has newfound hope in the country’s youth to bring on change. “The millennials who started the Lebanese revolution won’t stand for that kind of treatment.”

“Can they call on ending the kafala system, one of the greatest injustices in the world? If they don’t, I fear no one will,” she concluded in her report.

Stories of inhuman treatments of vulnerable migrant workers keep surging in Lebanon, a shame we, unfortunately, have to carry until the government decides to acknowledge its key role in ending that form of slavery. It is the least decent thing to do.

Until then, it remains the people’s main responsibility to act humanly towards their house helpers, while activists in Lebanon will keep fighting for the dreadful Kafala system to be abolished.