We’ve all heard of the tragic event that claimed the lives of many in 1912. The epic Atlantic crossing that never was.

We’ve sobbed and reached for the tissue box watching James Cameron’s romantic-drama about it.

The sinking of the unsinkable RMS Titanic!

According to journalist and researcher Michel Karam who authored Lebanese on The Titanic, the Lebanese survivor Chaanine George Wehbe had counted all the Lebanese aboard and said there were 165 passengers from Lebanon.

While it is hard to distinguish the true number, other researchers agree that there were roughly 100 Lebanese on the vessel, maybe even more.

Stories have been told about the Lebanese survivors, some true, other completely made up, and perhaps a bit inspired by the film about Jack and Rose.

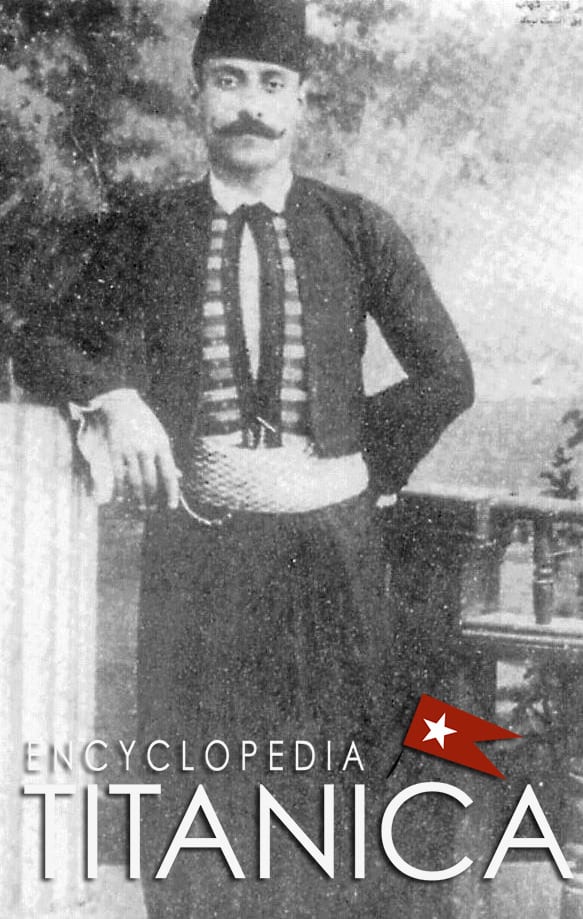

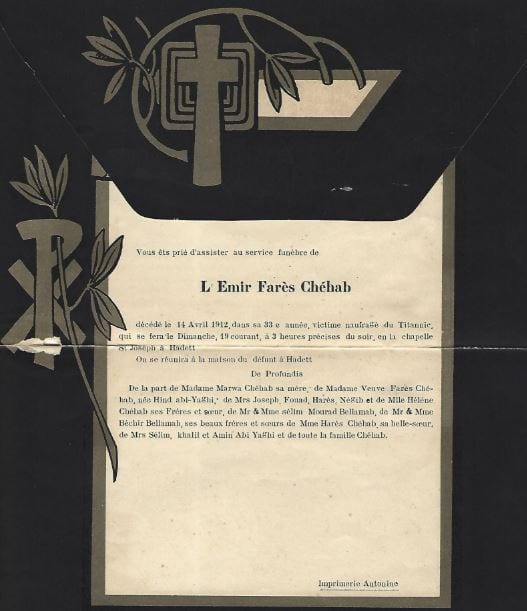

But here is a true story of one of the Lebanese passengers on board, the Emir Fares Chehab.

The961 got together with his grandnephew, Hares Chehab, to bring you the story of Emir Fares.

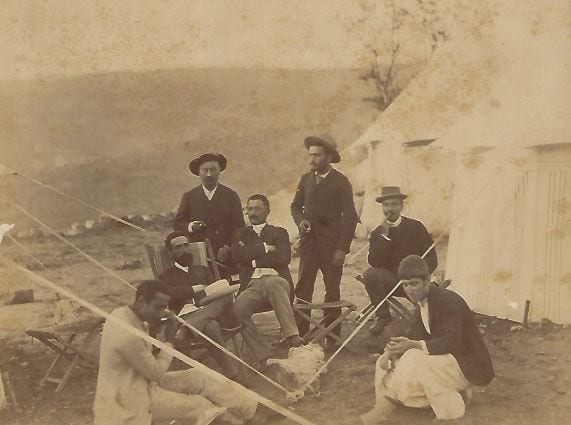

In 1879, prince Fares Chehab was born into a prominent Lebanese family that traces its lineage back to the Quraish tribe of the Prophet Muhammad.

He was the first conductor of the Beirut Chamber Orchestra as well as a solo violinist.

Coming from the noble Chehab family as an Emir, and holding the title of a Maestro, it is hard not to wonder why Fares chose to leave Lebanon.

However, Hares shared that his grand-uncle Fares “found himself confronted with a personal situation that could have had extensive and adverse consequences on his immediate family and other notables in Beirut, and getting away from it all was the best possible option.”

It could have also been that Fares felt moving abroad would help him develop his passion as a talented musician, thought Hares.

“America had universal appeal as the land of boundless horizons and possibilities…”

-Hares Chehab

Or could there have been another reason?

The answer probably lies in the mystery of why the Emir was registered among the 3rd class passengers aboard the Titanic. Surely someone of his stature could sail first class.

In fact, that record was puzzling to even the Greenwich National Maritime Museum in London that proceeded in 1996 to contact Hares’ sister Youmna Asseily in the United States.

The prestigious museum wanted to understand why an Emir (listed as Shihab) was in the 3rd class.

“Through research and correspondence between Greenwich and Boston, the Museum suddenly stumbled upon an answer unknown to us,” Hares told The961.

Apparently, they found an exchange of letters between Fares and a young American missionary lady who he had met during her travels to Lebanon. It became known that she had been helping Lebanese families emigrate to America.

“It seems she was waiting for his arrival there and had asked him as a favor to chaperone a group of Lebanese emigrants whose trip to America she had organized,” said Hares.

“It looks like he was the perfect gentleman, or she was particularly charming, and therefore booked himself with her protegees in 3rd class.”

The Emir along with the Lebanese passengers boarded in Cherbourg, unaware of their doomed fate.

According to survivor’s accounts relayed to Fares’ siblings and passed down to Hares, “witnesses recalled a ‘gentleman, remarkably composed, wearing a Turkish hat and dressed in black tie.’ From their descriptions of his features and the Turkish hat, we have assumed it was him,” Hares believed.

“They also said that, throughout the vessel’s ordeal, he stood next to the band as they played on the deck, and eventually let himself go down with the ship… This would be both fitting as an artist and as a Chehab!”

Today, Emir Fares Chehab’s funeral notice is displayed in the ground floor’s music room of the Spanish embassy in Beirut, which was formerly the Chehab family palace in Hadath.