The Prime Minister of Lebanon, Saad Hariri, resigned last month, parliamentary consultations have been postponed again, and President Michel Aoun and the rest of the political class are unwanted by the people on the streets. The protesters have asserted once and again their will to remain in their demonstrations and sit-ins until their demands are achieved.

The country is spiraling into the unknown with every new sunrise and everyone is asking the usual question… What’s next?

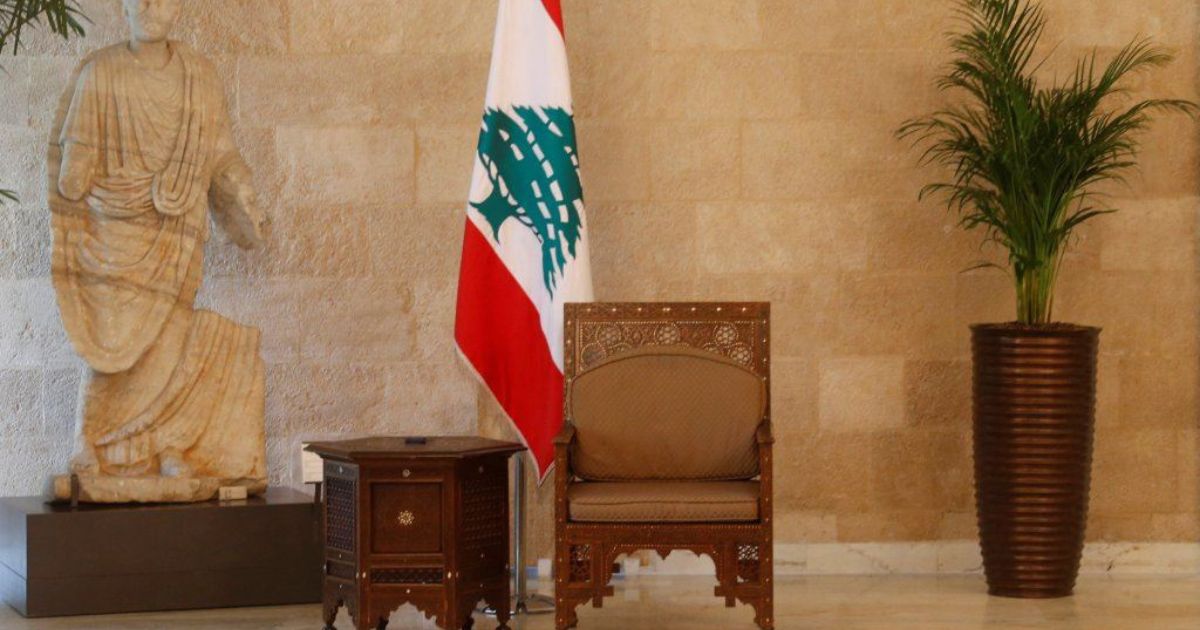

Really, what is the next step here? The revolutionaries want the entire Lebanese political system reformed, but the inhabitants of this system don’t seem to be going away anytime soon. Is there no way to force those who remain atop their thrones to step down and yield to the loud calls and the rising fists?

Maybe not.

But there is a way to further press them to give the people their right to take back control of their country, and it doesn’t contradict the so-far peaceful methodology of the revolution. This idea has a proper name, and a catchy one at that: “A Shadow Cabinet.”

And no, it has nothing to do with ghosts or the supernatural. Read on to understand what a shadow cabinet is and how it can be a way for the revolution to get closer to realizing its main goals.

What is a shadow cabinet?

Here’s a general definition of a shadow cabinet (or shadow ministry), which has also been recently referred to as revolutionary cabinet/government in Lebanon’s case:

A shadow cabinet is a group of politicians who hold a political post with their party, but whose party is not officially in government (that is, an opposition party). A member of the shadow cabinet is a shadow minister. The leader of a shadow cabinet is called the Leader of the Opposition.

Politicians? Party? Leader? Before you bombard me with criticism, hear me out. Although a generic shadow cabinet, like the ones active in the UK or Canada, is almost perfectly described by the above piece, the version discussed in this article is not a generic one.

Instead, this is a slightly tweaked version of the shadow cabinet. To avoid confusion, I will refer to the intended version with the convenient name: “Revolutionary Cabinet.”

What’s different between a regular shadow cabinet and the not-yet-in-action revolutionary cabinet is three main parts: The politicians, the party, and the leader.

This idea is similar to the shadow youth cabinet that was first proposed by the late Gebran Tueini before his assassination, which was decreed by the Lebanese Council of Ministers in 2006 and of which two were formed between 2007 and 2008. It consists primarily of university students and people of competence and expertise.

The revolutionary ministry will not have a leader or president and will be the mouthpiece of the movement through which proper negotiations can take place with the official authority with all its parties.

Needless to say, such a cabinet would not be an officially recognized part of the government or authority but would serve as an opposition to the latter, publicly scrutinizing and criticizing its work while proposing competent, enhancive ideas for the public to judge.

Then how exactly would it help?

Having a revolutionary government would place immense pressure on politicians active in the Lebanese political scene because its goal is to present itself to the people as the better choice for the country to be considered in future elections.

The pressure may also have another powerful effect on the current government; a strong critic that speaks its language and exposes any attempts of manipulating or hiding facts from the people, thus possibly forcing the government to work with honesty. If realized, such a scenario would, in turn, reap sensible reformation.

Therefore, the lack of constitutional power does not mean that the revolutionary cabinet has no power at all, but that it holds the effective power of the watchful, judging eye that can have an effect on anyone; even the sturdiest of politicians.

A source close to the Kuwaiti Al-Anbaa newspaper revealed last week that Lebanese revolutionaries were considering the formation of a revolutionary government to manage the affairs of the popular uprising.

That is in case President Michel Aoun does not initiate binding parliamentary consultations within one week; a period that has already expired.

Whether or not we will see such a government on the Lebanese stage soon can only be known with time.