It is estimated that every week, two migrant domestic workers die in Lebanon, by botched escape attempts, or suicide, according to the General Security’s intelligence agency.

Why would there be so many escape and suicide attempts among these workers?

Because of the terrible abuse that many of them endure on a daily basis as an inevitable result of the country’s unjust sponsorship system known as kafala (literally, sponsorship).

Kafala: A Two-Year Lockdown

The kafala system is the set of administrative regulations, customary practices, and legal requirements that bind a migrant domestic worker to a sponsor (employer), for the specific period determined by an employment contract.

As per the Lebanese Labor Law, migrant domestic workers can only legally work in the country as long as they are contractually bound to a local sponsor, with which they sign the Standard Unified Contract after their arrival in Lebanon.

A quick look at the contract reveals that it grants the employer excessive authority over the worker, who is, by law, explicitly excluded from the standard labor protections given to the other classes of employees.

Death by law

This means that migrant house helpers do not have the right to a minimum wage, overtime pay, compensation for unfair dismissal, social security, parental leave, and other basic safeguards.

The worst part is that their legal residency is directly tied to their contract with their employer, and they are legally prohibited from revoking the agreement without the consent of the sponsor.

The moment a worker walks away from their employer’s sponsorship without the latter’s approval, they automatically become an illegal alien and can be faced with fines and imprisonment.

Simply put, the kafala system renders the worker completely reliant on the employer.

This dependency makes it very troublesome for foreign domestic workers to defend themselves in case their rights are violated – and they often are.

And when such a violation does happen, the worker would often be cast into a very weak position if they decide to take the matter to court, due to the fact that the kafala system, in its nature, heavily favors the sponsor.

Evidently, this cruel system makes it easy for employers to force their workers into staying under their control, even in the most abusive environments and working conditions; otherwise, the worker risks losing their migration status.

More Ways Kafala Suppresses Migrant Workers

In addition to the latter, the kafala system sets no national wage minimum for migrant domestic workers. Instead, the workers are often subjected to discriminatory wages based largely on their ethnicity/nationality.

As per the Standard Unified Contract, the worker is supposed to work a maximum of 10 hours a day, with frequent short breaks in between them. That is in addition to at least 8 hours of rest each day.

However, there is really no way to force an employer to commit to these standards, which are already too harsh considering the small wages that the majority of workers get paid for them.

The weekly 24-hour rest period specified in the contract is also neglected in many cases, and the same can be said for the worker’s right to a once-a-month phone call at the employer’s expense.

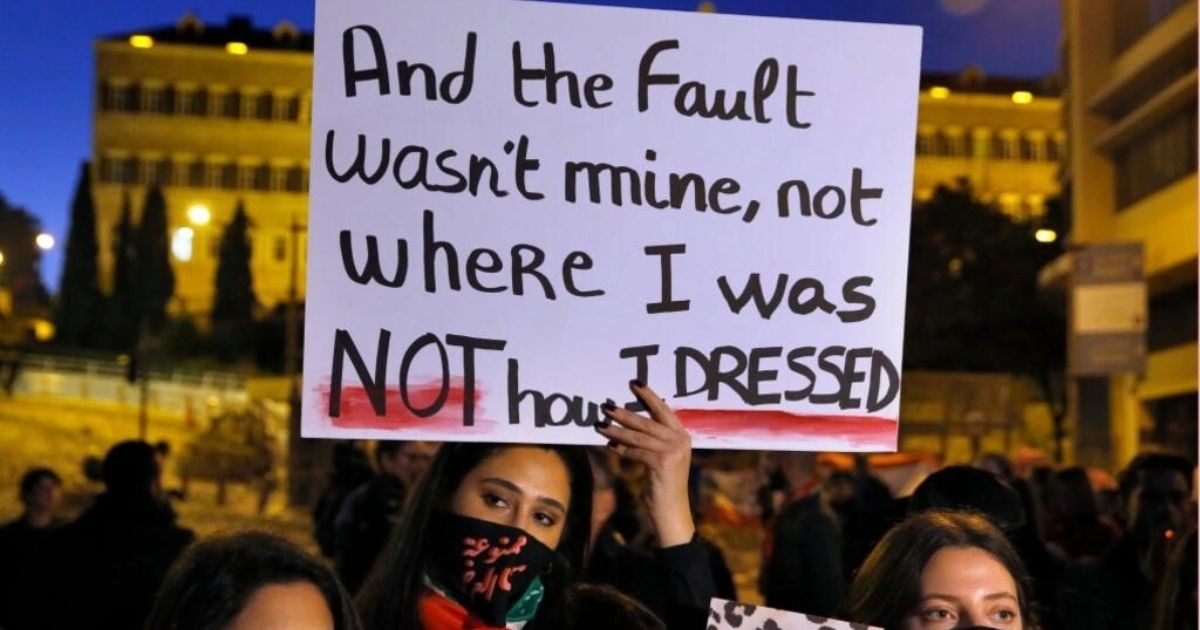

With all that injustice and more, the kafala system “has trapped migrant domestic workers in a nightmarish web of abuse ranging from exploitative working conditions to forced labor and human trafficking,” as Amnesty International puts it.

“We Can’t Breathe”

The migrant house helpers, which are majorly women, are frequently forced to endure illegal, yet unmonitored abusive acts, such as the confiscation of passports, withholding of wages, as well as verbal abuse and physical violence.

A common form of abuse exercised against these workers is forcing them to work long periods of exhaustive labor with very little or no breaks, accompanied by strict control over their freedom of communication and movement.

That is not to mention the rampant cases of violations of basic human rights, such as not providing the worker with proper food and/or accommodation.

With all of the above said, it’s clear that the system does not come close to being in sync with the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), of which Lebanon is a part, let alone with general human rights principles.

To top it all, as per Lebanese laws, foreign domestic workers have no legal right to form associations, which makes it even more challenging for them to advocate and defend their own rights.

This, and more, is what provokes local and international NGOs and activists to call for the complete abolishment of the kafala system and the introduction of a new one that protects the workers’ rights, especially the right to revoke a contract at will, without losing immigration status.

More recently, the dollar crisis has exacerbated the migrant workers’ suffering. At this time, most are either being paid in the devaluing Lebanese pounds or not paid at all and savagely kicked out to the streets by their sponsors.