Lebanon has long witnessed high-pitched sectarianism among political leaders and parties.

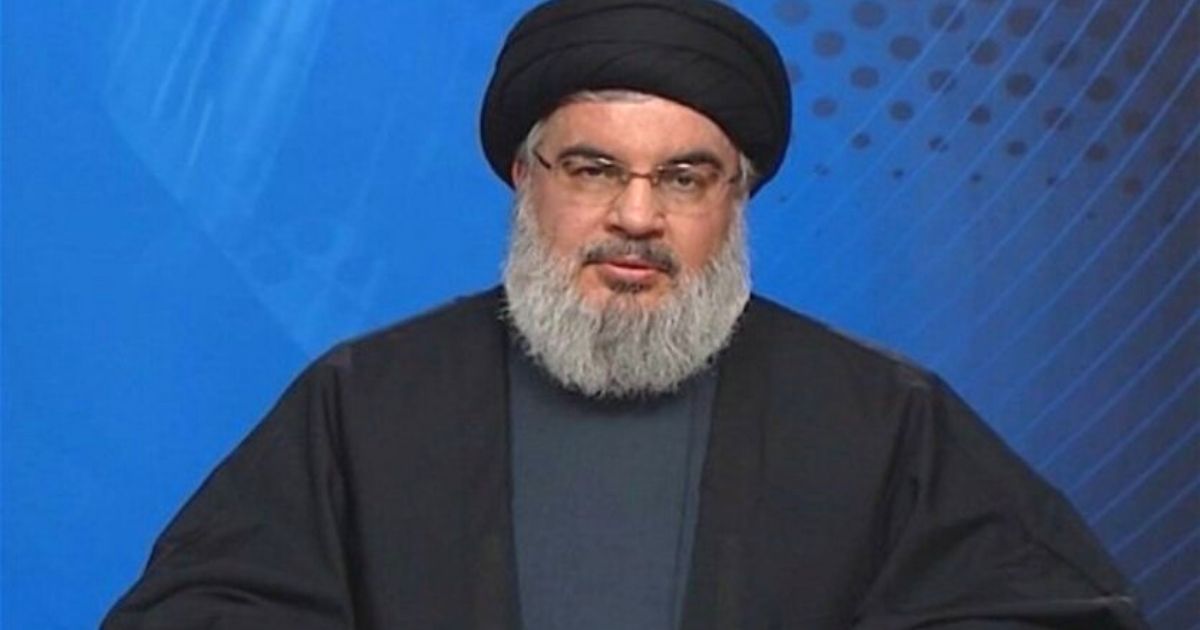

Most recently, the conflict between Samir Geagea, president of the Lebanese Forces Party (LF), and Hassan Nasrallah, Secretary-General of Iran-backed Hezbollah, has once again tightened sectarian nerves among their supporters.

This feud came in response to the Tayyouneh events, during a protest led by Hezbollah and Amal Movement against Judge Tarek Bitar, lead investigator of the Beirut port explosion.

However, the quarrel started earlier, a couple of weeks leading to the Tayyouneh events, on social media, with both sides and their partisans shooting tweets against each other with accusations intensifying, along with the escalating emotions.

On October 14th, on their way to the justice palace, Hezbollah and Amal protesters walked through a district known to be a hotbed of the Lebanese Forces (LF), chanting sectarian slogans.

While it is unconfirmed to date how the clashes started, and which side initiated it, they resulted in bloodshed, with 7 people killed, some 60 wounded, and serious property damages.

Nasrallah accused the LF of sparking the gun battle. In his first speech after the clashes, he avoided mentioning the LF’s leader by his name. Instead, he indirectly yet clearly blamed him.

“We [Hezbollah] do not represent any threat or danger to you [Lebanese]. Rather, the danger to you is the Lebanese Forces and its leader,” Nasrallah charged.

Flexing Hezbollah’s muscles, he warned that he commands 100,000 fighters, a serious threat that wasn’t lost to anyone.

It was, though, shocking for the Lebanese in general since he wasn’t addressing the threat to Israel – the alleged reason for the existence of his ‘army’ – but rather to the Lebanese audience.

He also bluntly threatened Geagea, saying: “Don’t miscalculate. Be wise and behave. Learn a lesson from all your wars and all our wars.”

“I advise the Lebanese Forces party to give up this idea of internal strife and civil war,” he threatened and accused simultaneously.

Nasrallah went even further, seeking to convince the Lebanese Christians that their rights are protected by Hezbollah’s Christian ally and LF opponent: the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM).

Geagea had denied any involvement in the Tayyouneh events. He has also denied more recently having been summoned to testify at the Military Court. He, however, declared that he will give his statement if summoned and only if Nasrallah is summoned first.

He described Nasrallah’s speech as “full of fallacies, lies, and rumors.”

He rejected the accusations and claimed that he does not know who fired the first bullet in the Tayyouneh events, and emphasized that the first wounded people were residents of Ain El-Remmaneh, which is known as a Christian district.

Responding to Nasrallah’s gloating about the number of his fighters, Geagea said, “The Lebanese Forces do not have fighters. We have 30 or 35 thousand members who are very clear and present in Lebanon and outside Lebanon… We do not bet on war, we do not want it, and we do not have an armed organization.”

He added that “Nasrallah is going through a very big predicament as he has been rejecting the judicial investigation [of the Beirut explosion] for 4 months… They [Hezbollah and Amal] don’t want an international investigation, and they don’t want Fadi Sawan or even Tarek Bitar.”

Judge Fadi Sawan was the initial lead investigator on the Beirut Blast case and was pressured to quit under threats and political interference. Judge Tarek Bitar was then brought in to replace him.

Both Geagea and Nasrallah, each with a different purpose, compared the Tayyouneh scenes to the infamous ones of May 7, 2008, triggered by an 18-month-long political crisis and the government’s decision to dismantle Hezbollah’s telecommunication system.

The date is remembered as the violent conflict that almost led to a civil war.

Back then, Hezbollah turned its weapons to fight its Lebanese opponents inside Lebanon. Hundreds of its fighters took to the streets, shut down media outlets, destroyed offices of their political opponents, and seized control of west Beirut.

Military confrontations and battles quickly expanded between the Shiite fighters and Druze and Sunni fighters in Mount Lebanon, Beirut, Tripoli, and other parts of the country. A fierce military confrontation that was about to ignite a devastating sectarian war.

The conflict was brought to a final stop by the intervention of the Arab League which brought about the Doha Agreement 2008, on May 21.

The Tayouneh clashes, Nasrallah-Geagea feud, and comparison to May 7 have further inflamed existing sectarian tensions as evident in countless tweets by Hezbollah and LF supporters.

It is no secret that Lebanese political leaders have always relied on fueling sectarian emotions and enabling dividedness in order to empower and/or justify their own positions and ensure the votes of their communities.

A study by the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies and researchers Melani Cammet and Dominika Kruszewska demonstrated that a shared religion is the strongest factor that influences the likelihood of supporting a candidate.

Being fed the idea that political parties and the overall sectarian system are there to protect them and their sects, as the study indicates, people willingly give their loyalty and trust to their leaders.

“Voters assume that an in-group member will have the interests of the group at heart,” the study notes.

Likewise, in her research, anthropologist Lara Deeb asserts that “sect matters to a lot of people in their daily lives, not only in relation to politics, networks, legal status, or the material realm but in their interpersonal interactions.”

However, the new phenomenon of the rise of secular movements in Lebanon’s universities and syndicates and them gaining seats in their elections has materialized as a serious obstacle for sectarian-driven politicians.

Political parties, including Hezbollah, LF, and FPM, have lost significant popularity since the onset of the Lebanese Revolution and furthermore after the Beirut explosion.

Political experts suggest that regaining the loyalty of their communities as it used to be is initially the main aim of this escalating open feud.

They are linking the rising sectarian tension that Lebanon is witnessing to the coming Parliamentary elections 2022 as people tend to revert back to their communities’ leaders due to fear and insecurities.

In front of that attempt, however, is the growing campaigns of the Lebanese revolutionaries and activists against voting for partisans of the existing political leaders, which they deem responsible for the collapse of the state and the crises they have been hardly enduring.

It does beg the question of which will prove stronger in the coming elections, the politically fueled sectarianism or the people’s determination for a better Lebanon.