In the early 20th century, a defeated young boy dropped out of school and started working to support his family.

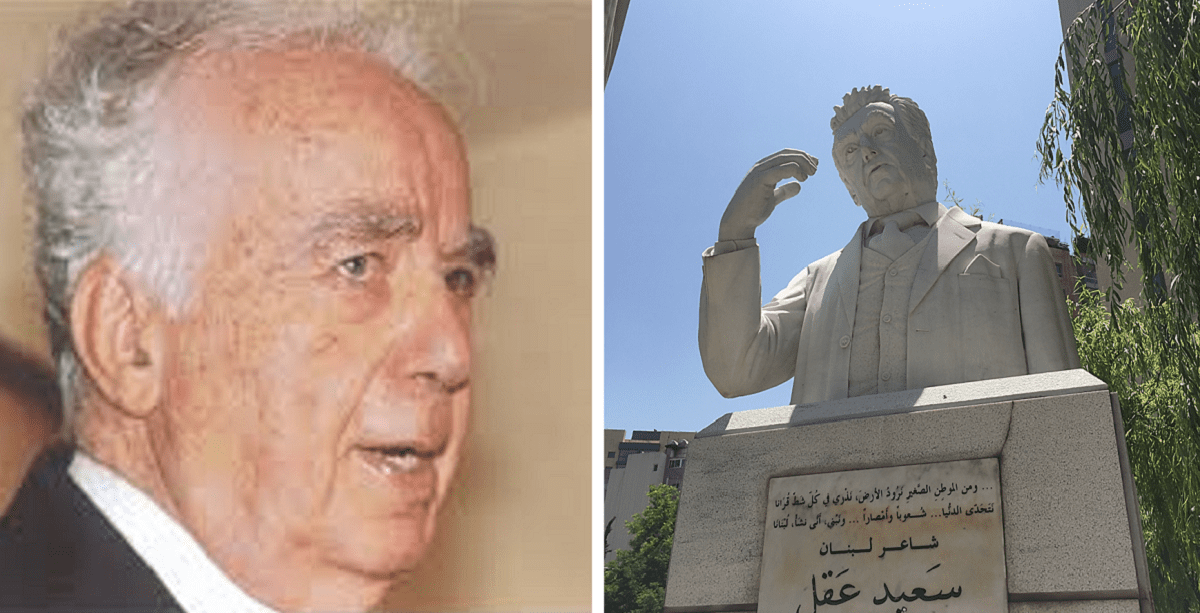

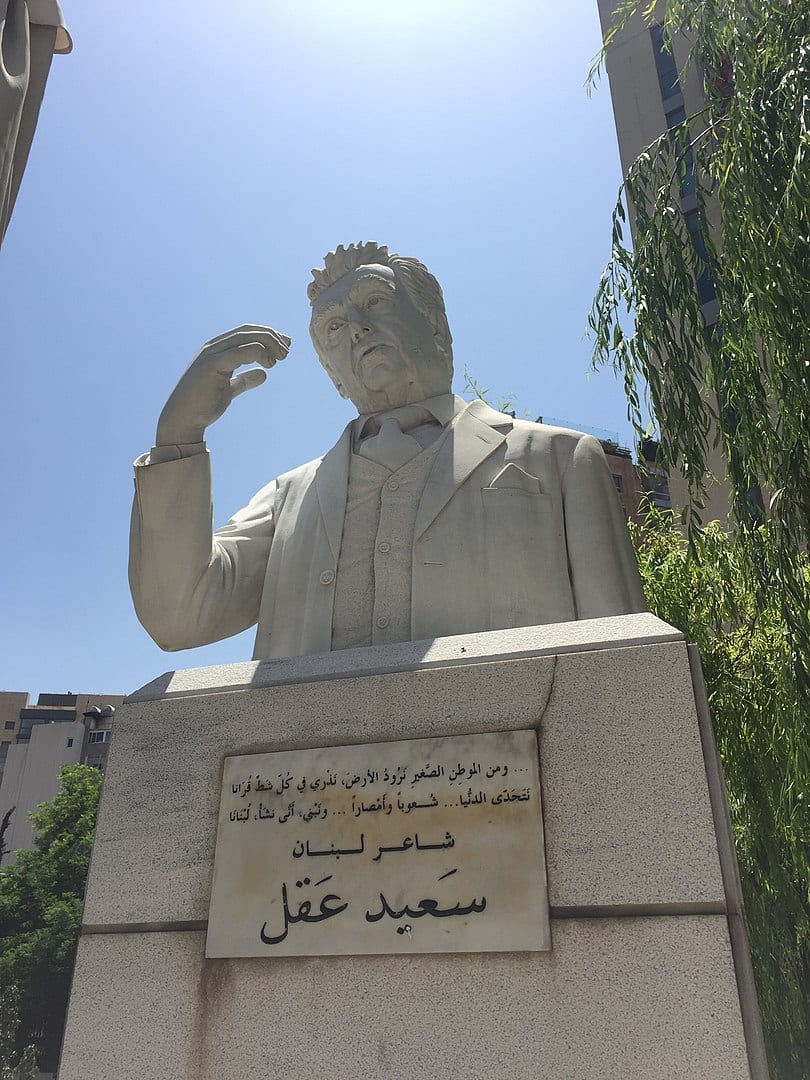

Little did this boy know, he would grow up to shine as one of Lebanon’s greatest writers, poets, and intellectuals; this is the story of Said Akl.

Said Shibl Akl was born in Zahle in 1912. As a young student, he spent his elementary and secondary years in two different Evangelical schools, but his secondary education came to an abrupt end in 1927.

When he was 15, his father Shibl was hit by a terrible financial crisis that left him unable to sufficiently provide for his family.

Shibl sold his lands and went bankrupt. His other son, called Akl, had to immigrate to the United States to help.

A humble beginning

Meanwhile, young Said was forced to drop out of school and seek a job to do his part and help his family. He got into writing and teaching early-on in his life, even though he wished to become an engineer.

In 1930, he left Zahle and settled in Beirut where he began to work as a part-teacher, part-newspaper editor. He worked for several newspapers, including Al-Barq, Al-Sayyad, and Al-Maarad.

By the time he was 24, Akl’s honest, unique writings were already drawing much attention, praise, and popularity, and his reputation continued to grow as the years progressed.

He resumed his education in 1939 and went on to study literature, theology, and Islamic history, but he did not receive a degree for his university education.

This did not stop him from becoming a remarkable and admired lecturer, however.

He proceeded to give great lectures on various topics, including theology and Lebanon’s intellectual history, in many Lebanese universities and colleges, while maintaining his positive momentum as a journalist.

Unsurprisingly, Akl was an obsessive reader who came to learn a lot about the world’s different cultures and civilizations, most notably the Phoenician civilization, which had an enormous effect on his life; more on that later.

An explosion of brilliance

He also consumed and fell in love with endless pages of literature from Lebanon and around the world, and went on to create his own masterpieces in the realms of prose, poetry, and theatre.

His first play, Bint Yifta’h (1935), was the first of its grade and quality in Lebanon and became an award-winning classic.

His next play, Fakhreddine, which is a historical musical, was an even greater success that facilitated the growth of his fanbase.

Meanwhile, he worked on what he became known for the most; poetry. What followed in the later years was an explosion of brilliance that propelled Said Akl into local and regional fame and revolutionized Arabic poetry.

Throughout his extraordinary career, Akl wrote over 5,000 verses of poetry, both in Lebanese and Classical Arabic, that became an essential part of Lebanon’s cultural and intellectual history. He also wrote French poetry.

What helped draw more popularity to his work was the fact that Fairuz sang many of his poems after the Rahbani Brothers turned them into songs, which included the famous Bhibbak Ya Libnan (I love you, Lebanon), among numerous others.

Notably, Akl was the person who gave Fairuz her famous nickname: “Lebanon’s ambassador to the stars.”

Some of his most recognizable poetical works include Al-Majdaliyyah, Rindalah, Ajraas-al-Yasmeen, and Yara.

Said Akl’s plot twist

Despite the fact that much of Akl’s exquisite prose and poetry were written in Classical Arabic, he later turned his back on the language, as well as on Arab nationalism, of which he had previously been a big advocate.

Returning to Fairuz, the extraordinary singer also sang some of Akl’s beloved pan-Arabist songs, the likes of Zahrat al Madaen, about Jerusalem, Ghannaytou Makkah, about Mecca, and Saailiini ya Sham, about Damascus.

It’s worth noting that, during his early years, it is said that Said Akl was the one who wrote the anthem of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party.

However, Akl denied that he even knew the party’s leader, Antoine Saadeh, and dismissed the claim that he wrote the anthem and handed it to him, in a 1992 Annahar interview.

After avidly supporting and identifying with Arabism, the poet’s cultural and political stances shifted dramatically.

He adopted a unique doctrine of Lebanese nationalism that was accompanied by a strong resentment toward the Arab identity of Lebanon.

In the late 1960s, he said that literary Arabic would vanish from Lebanon, and even said that had he had the time, he would have translated all of his Classical Arabic work to the Lebanese dialect exclusively.

The switch to Phoenicianism

In 1972, he helped found the Lebanese Renewal Party, which was a non-sectarian party that adhered to Lebanese Nationalism, and later became the spiritual leader of another nationalist movement, Guardians of the Cedar (Herrass El-Arz), during the civil war.

On a side note, one of his political aspirations was to become the president of Lebanon.

Interestingly, Said Akl’s strong devotion to Lebanese Nationalism pushed him to set out to reform the whole of the Lebanese language and sever its ties with Arabic entirely.

Although he did not ignore the latter’s influence over the Lebanese language, he affirmed that the Phoenician language had an equal, if not greater, influence over it.

The Arabic language is destined to become extinct. And if I have become one of the great Arabic-language poets, it is precisely so that I can have the authority to express this idea.

Said Akl

He was also a firm believer that Lebanon was the inheritor of the Oriental civilization and a promoter of the Phoenician heritage and identity of the Lebanese people.

So, he designed an independent “Lebanese language,” based on Latin alphabets, and deemed it an evolution of the Phoenician Alphabet.

The new language contained 36 letters and was shaped to specifically suit Lebanese phonology.

While he did not translate all his writings into the Lebanese language as he said he wanted to, he did translate some, including his famous poetry book Yara.

An unforgettable chapter in the Lebanese story

Akl even published a newspaper in his proposed language, called Lebnaan. (It also had an Arabic version).

Evidently, his change of heart was not restricted to language and culture; his political orientation viciously opposed Arabism.

In 1982, during the civil war, he became an even more controversial figure when he openly advocated for the extraction of the Palestinian presence in the country.

Regardless of his unpopular political views, what Said Akl left behind is nothing short of a national treasure that will continue to define and shape the Lebanese story forever.

To this day, his words, whether in the Lebanese dialect or Classical Arabic, remain a standard for Oriental art and literature, admired and enjoyed, in print and music forms, in both Lebanon and the Arab World.

The literary genius lived a long life after sharing his rare gift with the world.

He lived on to become a centenarian and passed away on the 28th of November, 2014, “peacefully,” his friends said, concluding 102 epic years of extraordinary achievements.

About him, it has been said: “Said Akl, the man who loved Lebanon more than himself.”