Despite its relatively small size, Lebanon is known to host diverse populations and ethnicities. But perhaps one of the least talked-about community is that of Bedouins, whose passionate attachment to their culture and history brings them great pride and, sometimes, pain.

Bedouins are nomadic Arabs who have had a prominent presence in the Middle East for hundreds of years, including in Lebanon, though less strongly compared to neighboring countries.

Most Bedouin clans and tribes that live in Lebanon and the region originated in the Arabian Peninsula.

While some came to Lebanon with the Muslim conquests, more than 1,000 years ago, others arrived in more recent decades, most commonly from Syria.

Lebanese Bedouins: Modernity Against Tradition

Though the numbers vary, more than 30,000 Bedouins are estimated to be living in Lebanon today. They are mostly concentrated in the Beqaa region and the north, but some also live in coastal areas in Beirut and south of it, such as in Khalde.

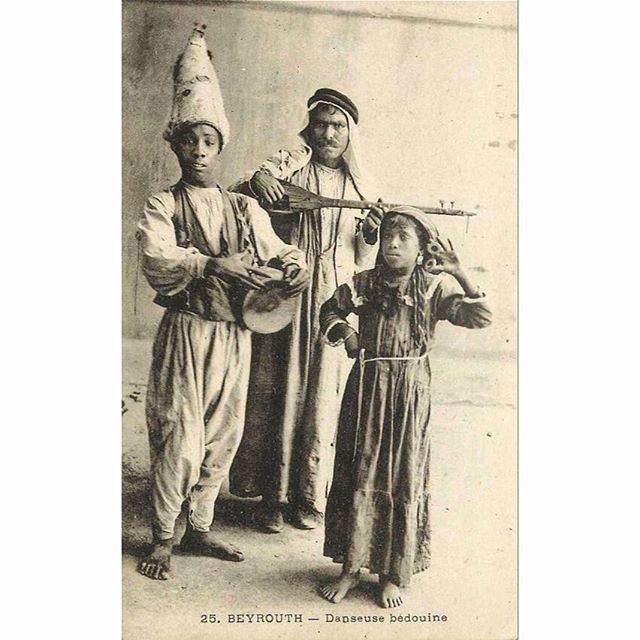

Bedouins are generally known for their strong attachment to tradition, which most tribes in Lebanon have maintained throughout the decades.

However, their commitment to their ancestors’ simple, nomadic way of life has been greatly challenged by the rapid development and modernization of the world around them.

Today, the level of adherence to the old ways that have been passed on over many generations varies greatly from one tribe to another in the country.

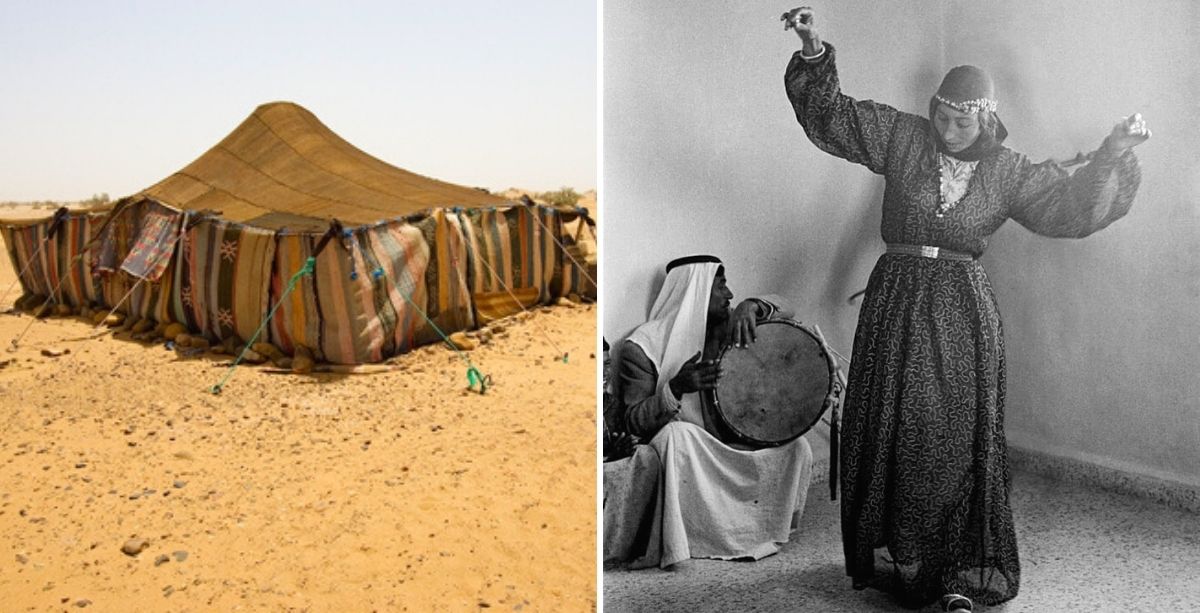

Some tribes have held on tightly to their traditions and mobile lifestyle, which relies heavily on cattle and grazing; they live in tents in open land – bitter coffee constantly within reach – and regularly move around to feed their animals.

However, even those “conservative” tribes have been affected by the changes around them. One good example of this manifests during Ramadan (the vast majority of Bedouins are Sunni Muslims).

Iftar and Suhoor for Bedouins in the old days was often very simple: Staple meals included dates with yogurt and grind wheat with milk. Also, bread was most commonly made out of corn or barley.

Today, however, the Bedouin food scene, especially in Ramadan, is very similar to the one commonly seen in regular Lebanese households: meat, soups, salads such as tabbouleh and fattoush – even fries – are commonly consumed.

Photo: Carla Haibi

Regular khebez bread is also commonly bought or produced by the nomadic tribes using wheat flour purchased from the market.

On the other hand, other tribes are more indulged in the modern lifestyle, balancing modernity with tradition; they have left the mobile lifestyle behind, but their sense of tribal belonging remains dominant.

In most cases, the authority of a tribe culminates in its leader, who usually enjoys extensive privileges that go into solving conflicts and making various decisions for the tribe, in accordance with the highly-revered Bedouin customs.

One interesting and almost-sacred tradition that continues to be relevant to a certain level in many Bedouin clans and tribes today is the mandatory protection of those who seek protection.

Photo credit: UNHCR/A.Branthwaite

According to this tribal custom, if anyone – even an unknown outsider – comes to a member of a tribe for protection, he is shielded so fiercely that the guardian can go as far as to sacrifice himself for the cause.

The Challenge

Traditions like these are partly why Bedouins in Lebanon are generally overlooked and marginalized, even though many of them carry Lebanese citizenship and identify as natives of the country.

The head of the Arab Tribes Union in Lebanon, Sheikh Jassem Al-Askar, once told MBC that clinging to tribal customs and traditions “is civilization.”

“This civilization and this concept and this culture that I have, if I want to explain it to civil society, they might not understand it. But if you go to the foundations, they are the basis of everything, the logic of life, even the foundations of the judiciary are taken from 80% of the customs of the tribes and clans,” he said.

Nonetheless, the Bedouins’ way of life – whether they continue to lead a nomadic lifestyle or have fused with the rest of society – has, over the years, generated negative stereotypes about them.

This, coupled with the fact that a large portion of tribe members are stateless due to various reasons, has caused many Bedouins to suffer unemployment and poor living conditions.

One of those reasons was some tribes’ fear of being conscripted by foreign armies after the first world war (they viewed joining these armies as treason), which caused them to dodge the census conducted at the time, costing them their naturalization.

The dire effects of statelessness continue to haunt Bedouins to this day.

Many stateless Bedouins in Lebanon are denied basic needs and services, such as employment and their children’s education, due to their lack of citizenship.

The fact that they are under-represented in the state makes it more difficult to get their voices across, especially since many reject the idea of joining political parties because of their strong sense of belonging to their tribe – the only party that matters to them.

You can find more exclusive content available only to The961+ members here.