Lebanon was traditionally known for its well-renowned international education system. In the 19th century, American and French missionaries set up schools and universities that became platforms for young Lebanese to further their studies abroad.

However, education has now become merely a fantasy for everyone but the rich class, that managed to keep enough of their wealth outside Lebanon.

According to Reuters, Lebanese medical student Lara Mustafa faces eviction from Russia and the end of her dream of becoming a doctor if her parents, hit by Lebanon’s worst financial crisis in decades, cannot send her money to pay for rent and expenses.

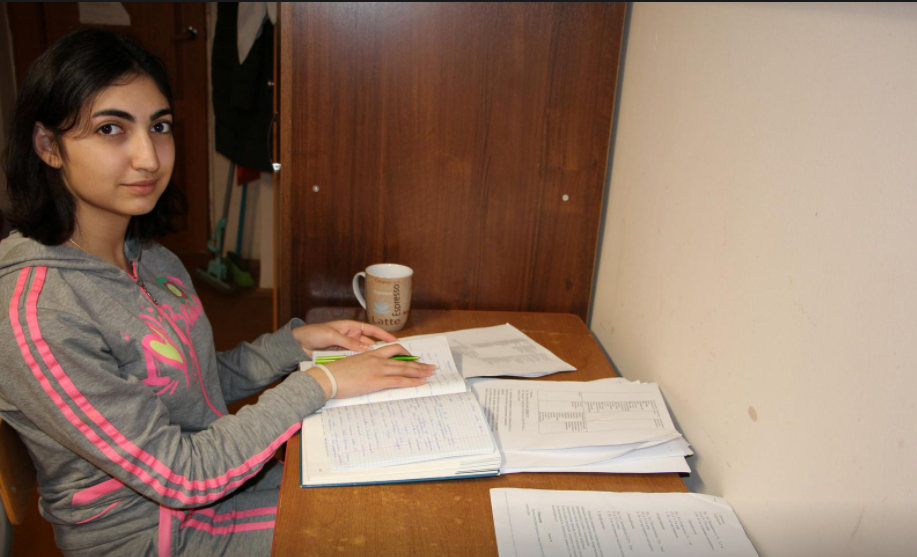

Lebanese medicine student Lara Mustafa is pictured at her dorm in Tver, Russia. Credits: Reuters

Lara Mustafa’s case is not unique among the Lebanese students abroad. Most are struggling to make ends meet even in relatively low-cost countries like Russia.

Wassim Hachem, 24, had to drop out from his fourth year of university in Russia to return to Lebanon and work as a delivery driver after his father lost his job and was no longer able to support him.

Unfortunately, the plight of our youth doesn’t end with these two cases.

Mustafa and Hachem are among thousands of university students caught up in Lebanon’s deteriorating financial crisis.

The extreme downfall of the country’s economy was prone to happen. The indications were all there yet nothing was done to prevent it. The people felt its sting across the country before the ruling class, which has been mostly shielded by their wealth. Businesses started to shut down…

The people hence revolted in 2019 with popular protests against the leaders whom they blamed for corruption and mismanaging the economy along with the country’s affairs.

The revolution of the people triggered the revelation of further mismanagements, including an insolvent banking system that had lent more than two-thirds of its assets to the central bank and state.

It went on to shut out all depositors from their dollar accounts, and limiting withdrawals, severely affecting people’s living conditions, businesses, and the economy.

And then came the pandemic and the several lockdowns, which have increased mass job losses and the collapses of more businesses.

Hundreds of businesses have shut down, the unemployment rate has increased as well as the poverty rate, and the students abroad are not being spared.

“You can say that my parents sank into debt in order to be able to send me money,” Lara Mustafa, 23, who is on a scholarship told Reuters from Russia via Zoom.

“I live in the student dorms. The system at our university is that if I can’t pay the dorm fees not only will I be evicted but I will be forbidden from taking the end-of-semester exam,” she explained. “Now, I live in austerity. Now, I calculate every penny.”

Mohammad Kassar, 22, told Reuters that he was into his fifth year of medicine in Ukraine, aiming to become a general practitioner. However, he was forced to return home in May because his father, whose furniture business went bust, was no longer able to transfer him money.

“It is a very harsh feeling to lose hope. In one year, I lost all the five years I have invested in. I lost the past, the present, and the future. I lost everything,” Kassar said.

Some parents of the thousands of Lebanese students abroad have been protesting outside Lebanon’s central bank. They are rightfully demanding to force commercial banks into implementing the government decree “Student Dollar.”

That law allows families with students abroad to transfer up to $10,000 a year at the official exchange rate of 1,500 LBP to the dollar to cover tuition and expenses.

Currently, parents and students say the law is being ignored, with banks and exchange dealers refusing to make transfers at the set rate and asking instead for the market rate, currently at around 8,300 LBP.

Central Bank Governor Riad Salameh told Reuters that “the law needs applications decrees from the government not from BDL.”

Lara’s mother Nidaa Hassan told Reuters that they used to send their daughter between $300-$700 a month but now manage much smaller amounts.

Lara’s mother explained that she had to remove her other children out of a private school in order to enroll them in a state school after her husband’s salary, which was worth $2,000 a month last year, is now equal to $370 due to the downfall of the Lebanese pound.

“We are not only borrowing money from here, but also from family abroad to be able to send her money. I don’t know how much debt we have accumulated so far,” Nidaa Hassan told Reuters with a heavy heart.

For over a year, banks have denied depositors access to money, even those with substantial funds cannot withdraw them.

We can confidently say that Lebanon’s middle class has vanished, squeezing people into only two categories; the rich and the poor.

As the economic crisis deepens in Lebanon, many like Nidaa blame ties between a powerful banking industry and the political elite for the country’s bankruptcy.

“Our dream now is to be able to eat, to put food on the table. Can we dream of anything else?” said Nadia Moussa, mother of Wassim Hachem.

It’s extremely unfortunate and unjust to watch Lebanese people struggle as they cannot get access to their bank accounts, while simultaneously billions have been smuggled out of the country by the political elite.